No, this isn’t about the Presidential election. It’s about the Missouri economy’s lack of economic vitality. And what I will show is that the lack of vitality is not a recent development.

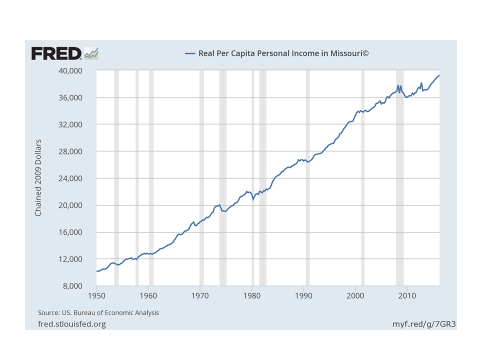

The two charts below tell the story. The first chart shows real personal income per capita (hereafter income), measured in 2009 dollars, for Missouri since 1950. In that year income stood at $10,168. By 2015 it had risen to $38,612. That almost-fourfold increase means that individuals today are, on average, much better off than they were in 1950. That’s the good news.

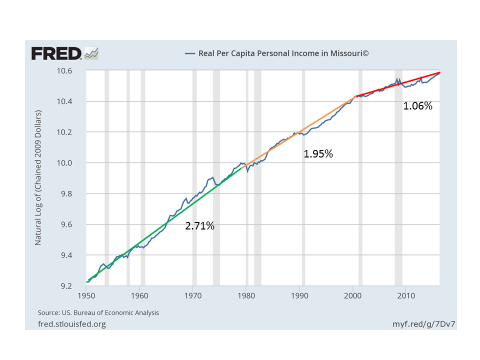

The second chart uses the same data, this time shown using a log scale for income. That means we can look at the slope of the line to better see how fast income has been growing over time. I have picked out what look to me like three fairly distinct stages of decline. The first runs from 1950 through 1979, and is highlighted with a green line. During these three decades Missouri income increased at an annual average rate of about 2.7 percent. The next period runs from 1980 through 1999 and is delineated by the amber line. During this period income in Missouri grew at an average annual rate of less than 2 percent, a notable drop from the previous period. The final stage, shown by the red line, is the period since 1999. So far in this century, income in Missouri has increased at an average rate of just slightly more than 1 percent per year. Income in Missouri today is increasing at about a third of the pace that it did 40 years ago.

If you are not used to thinking about growth rates of income, you might think that such changes are not really important. But they are, and some context shows why.

The slower the growth rate, the longer it takes for income to double. For the first period, that growth rate implies that income would double approximately every 26 years; for the second period the time to double increases to every 37 years; and the current growth rate means that it would take 68 years for income to double. The slower income growth means that it will take much longer for Missourians’ standard of living to increase.

Another way to think about what these growth numbers imply is to ask “What would income be today if the growth slowdown had not occurred?” Recall that income in 2015 was $38,612. Starting with the level of income in 1979, if Missouri's economy had continued to grow as fast as it had from 1950 to 1979, income today would be over $57,000. Or, suppose we use the 1999 level of income, which was $32,524, and ask what it would be in 2015 if income had increased at its slower 1980–1999 rate. The answer is about $44,300. In either case, income today would be appreciably higher that what it has turned out to be. Slower economic growth translates into lower standards of living.

The upshot is that ever-increasing layers of regulations that have impeded business formation, an increasingly complex tax structure that reduced incentives to work or expand businesses and, perhaps most important, a dysfunctional educational system all help explain Missouri’s slowing rate of income growth. If we continue down a current policy path that perpetuates this dismal performance, we will sentence future generations—at least those that choose to stay—to ever-diminishing standards of living.