With the release of inflation data over the past two weeks—consumer inflation (CPI) late last week and producer inflation (PPI) this week—glimmering signs of hope are emerging that 1970s and ’80s-era inflation may finally be in the rearview mirror. Predictably, this has led to crowing by the Biden administration that its policies deserve the credit, but the reality is quite the opposite. The administration’s glut of spending helped fuel the inflation to begin with, and the Federal Reserve has been cleaning up the mess over the past year after finally abandoning its use of the word “transitory” to refer to what clearly has been a persistent bout of inflation.

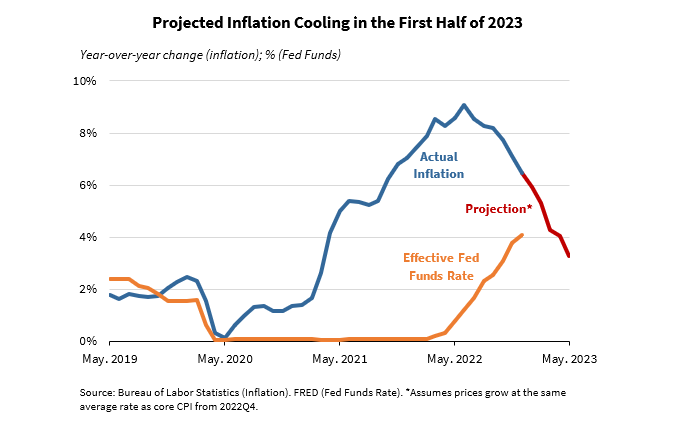

Beginning in early 2022, the Fed initiated a rate hike campaign that, to date, has taken the federal funds rate (which influences other interest rates in the economy) from 0% to over 4%. We now have evidence that the Fed’s rate hikes are beginning to bite. Consumer price inflation peaked in the summer of 2022 at over 9% and has been on the decline ever since, most recently hitting 6.5%. This lag between rate hikes and inflation dropping is common. Moreover, because the monthly inflation increases were so high in the first half of 2022 and have been considerably lower over the past few months, the topline year-over-year inflation readings are set to fall rapidly over the next several months—possibly even falling below 4% by early summer. The figure below visualizes a plausible path of inflation over the next few months.

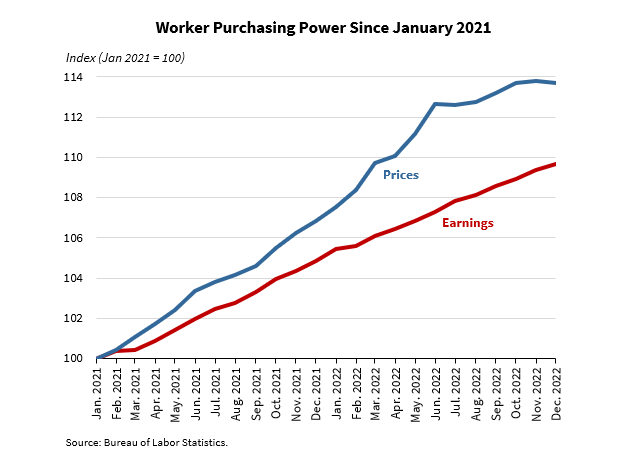

If this projection comes to pass, it would of course be very good news for families’ pocketbooks. Keep in mind, however, that inflation is declining despite the federal government continuing to spend too much money, and not because of any of the recently passed legislation. Absent the spending binge of 2021 and 2022, the United States would almost surely not have seen the decades-high inflation that has robbed families of precious purchasing power—an erosion shown in the figure below. Since the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act in early 2021, consumer prices have risen cumulatively by nearly 14%. During that same period, worker earnings have increased by less than 10%. This four-point gap marks a significant decline in purchasing power that is showing no immediate signs of reversing.

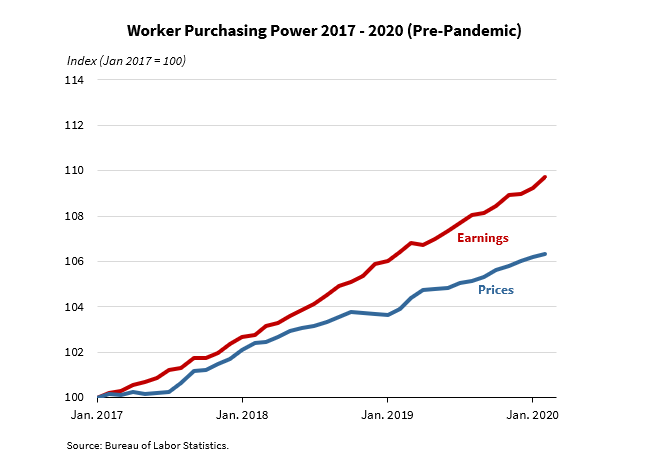

By contrast, if one looks at recent history—namely, the period between early 2017 and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic—earnings noticeably outpaced inflation, as shown in the figure below. In fact, inflation-adjusted median household income jumped by the most on record during that period, just as poverty rates hit historic lows. It is worth pointing out that economic gains of that size were not expected. Instead, the economy outperformed earlier projections from the Congressional Budget Office made prior to the pro-growth tax reforms passed in 2017 and the concerted effort across federal agencies to streamline and reduce the burden of regulations.

Looking forward, the good news is that inflation is likely to continue falling, and possibly at a faster pace over the next few months. Producer price inflation is also moderating, with the most recent core reading (which strips out volatile components related to food, energy, and trade services) coming in at “just” 4.6% year-over-year. However, it is important that we do not move the goalposts and lower the bar for victory. The objective clearly stated by the Federal Reserve—and to which Americans have become accustomed over the past few decades—is inflation that is 2% or less. For this reason, nobody should expect the Federal Reserve to immediately stop hiking rates—let alone begin to cut them—until inflation falls below the 2% threshold and stays there for a while. The Federal Reserve has signaled this much in its recent communications.

Of course, the timeline for finally taming high inflation could be significantly accelerated with a pro-growth, supply-side agenda that unleashed the productive capacity of the U.S. economy whereby businesses could meet demand without raising prices. If we conceptualize inflation as too much money chasing too few goods, one approach to reducing inflation is to take money out of the economy—exactly what the Fed is doing right now—while the other approach is to ramp up the amount of goods and services the economy produces. In light of divided government, substantial tax and regulatory reform is unlikely, but on the positive side, massive partisan tax hikes and spending bills are unlikely too. Inflation relief is (likely) on the way, but it is important to understand how we got here so we don’t end up making the same mistakes again.