REPORT

SEPTEMBER 2023

THE FUTURE OF MISSOURI’S WORKFORCE

By Susan Pendergrass

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Missouri’s workforce has been declining in numbers and quality, and trends in K-12 education indicate that’s unlikely to change anytime soon.

- Missouri’s labor force participation declined from a high of 71 percent in 1997 to just 63 percent in 2023, meaning that in 2023, there were over 700,000 Missouri adults not in school full time, not working, and not looking for work.

- The percentage of Missourians who have a bachelor’s degree or higher, after increasing for decades, has been declining recently, from 31.9 percent in 2020 to 31.7 percent in 2021.

- The percentage of Missourians who have a graduate degree has declined from 3 percent to 12.1 percent during the same period.

- The high point for public school enrollment in the last 20 years was in 2007, at nearly 895,000 students; since then there has been a steady decline. Although the state has recovered some students from the steep pandemic drop off, enrollment is down over 30,000 students from the 2007 high point and is expected to decline further.

- Although Missouri’s National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading scores have generally tracked to scores nationwide, they recently fell below the national average. In 2022, just 30 percent of Missouri’s 4th graders scored Proficient (generally the equivalent of being on grade level) or higher in reading. The results for math are similar.

- In 2022, there were 61,195 high school graduates in Missouri, and just 37,156 (61 percent) met one of the state’s college or career readiness benchmarks.

- Missouri’s participation in the College Board’s Advanced Placement (AP) program is well below the national In 2022, just 20.6 percent of Missouri high school students took an AP exam, ranking them 43rd among the 50 states, plus Washington, D.C.

- In the 2022 school year, 8,631 Missouri high school students received an industry-recognized credential (IRC) prior to graduation. In 2022, some 4,917 Missouri high school graduates met all of the requirements for a full career technical education (CTE) certificate, which was 7.6 percent of graduates.

- According to a report from Missouri’s Coordinating Board for Higher Education, postsecondary enrollment of recent high school graduates has declined from 35 percent in 2012 to under 30 percent in 2022. In addition, the mix of enrollment has changed from a higher percentage choosing a 4-year program to an even split between 2-year and 4-year

INTRODUCTION

According to a 2023 analysis of the “best states for business” by CNBC, workers are in short supply and there are more job openings than there are people to fill them across the country.2 That is certainly true for Missouri, which ranked 32nd out of the 50 states in the analysis.

What’s worse is that Missouri’s workforce, both in terms of quality and quantity, ranked 49th.

Missouri’s population is not growing. The education credentials of that stagnant population are also declining. The bubble of children in elementary and secondary schools has just about moved through the system.

Kindergarten cohorts started shrinking a decade ago, meaning that the number of high school graduates is about to do the same. Unfortunately, the percentage of these graduates who can read or do math on grade level is also declining.

Missouri should be enacting bold policies that attract and keep talent at all levels. Lawmakers should be using what is happening at the 4th and 8th grades as leading indicators and direct significant efforts at improving K-12 education, rather than the current approach of directing workforce development efforts at 25 year olds.3

The following analysis will describe the current Missouri workforce and how it has changed in the recent past. It will then describe K-12 enrollment trends and academic trends, as students today are tomorrow’s workforce. From there, it will project the state of the Missouri workforce in 2040 if Missouri simply stays the course. Finally, it will address several policies that could lead Missouri in a more positive direction.

A DESCRIPTION OF THE MISSOURI WORKFORCE TODAY AND IN THE RECENT PAST

Before we start discussing Missouri’s workforce, let’s lay out some definitions. According to Merriam-Webster, the workforce is defined as workers engaged in a specific activity or purpose or those potentially assignable to one. There is a separate definition for the labor force. The Bureau of Labor Statistics describes the labor force as those who are either working or looking for work; people actively looking for work or on layoff waiting to be recalled are considered to be unemployed.4 Members of the civilian, non-institutionalized population aged 16 or over who are not in school full time or looking for work are considered to be in the labor force.

In 2023, there were approximately 4.75 million adults in Missouri and just over 1 million were senior citizens, leaving 3.7 million of working age.5 At the same time, there were approximately 3 million Missourians employed in nonfarm jobs.6 The disconnect is explained by the fact that Missouri’s labor force participation had declined from a high of 71 percent in 1997 to just 63 percent in 2023.7 To reiterate, in 2023, there were over 700,000 Missouri adults not in school full time, not working, and not looking for work.

Of the 3 million jobs, about two thirds require only a high school diploma and the remaining one third require some type of postsecondary degree.8 According to the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center (MERIC), between 2018 and 2028 the percentage of jobs that require a high school diploma or less will grow by 2.8 percent, while those that require a bachelor’s degree will grow by 7.7 percent and those that require a master’s degree will grow by 11.1 percent.9

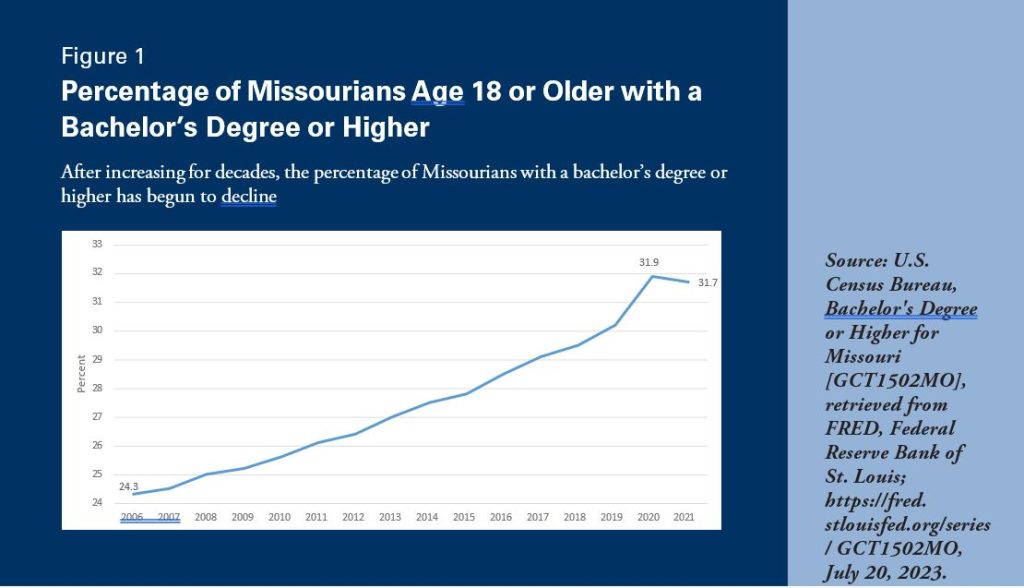

At the same time, the percentage of Missourians who have a bachelor’s degree or higher began declining recently after increasing for decades, from 31.9 percent in 2020 to 31.7 percent in 2021 (see Figure 1).10 And the percentage of Missourians who have a graduate degree has declined from 12.3 percent to 12.1 percent over the same period.11 These are very small changes, but the point is that these trends are going in the wrong direction. For perspective, according the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2021 37.9 percent of adults in the United States had a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 12.2 percent had a graduate degree.12

To summarize, the number of jobs in Missouri is projected to grow in the next decade, while the population is unchanged and labor force participation is declining.

Meanwhile, workers are not earning the credentials needed to keep pace with new job openings. Now let’s turn to the next generation of workers.

K-12 ENROLLMENT TRENDS IN MISSOURI

After a period of high growth in the 1990s, Missouri’s public school enrollment in kindergarten through 12th grade remained around 880,000 students until the pandemic of 2020.13 The high point for public school enrollment was in 2007, at nearly 895,000 students, and since then there has been a steady decline. Although the state has recovered some students from the steep pandemic drop off, enrollment is down over 30,000 students from the high point and is expected to decline further.

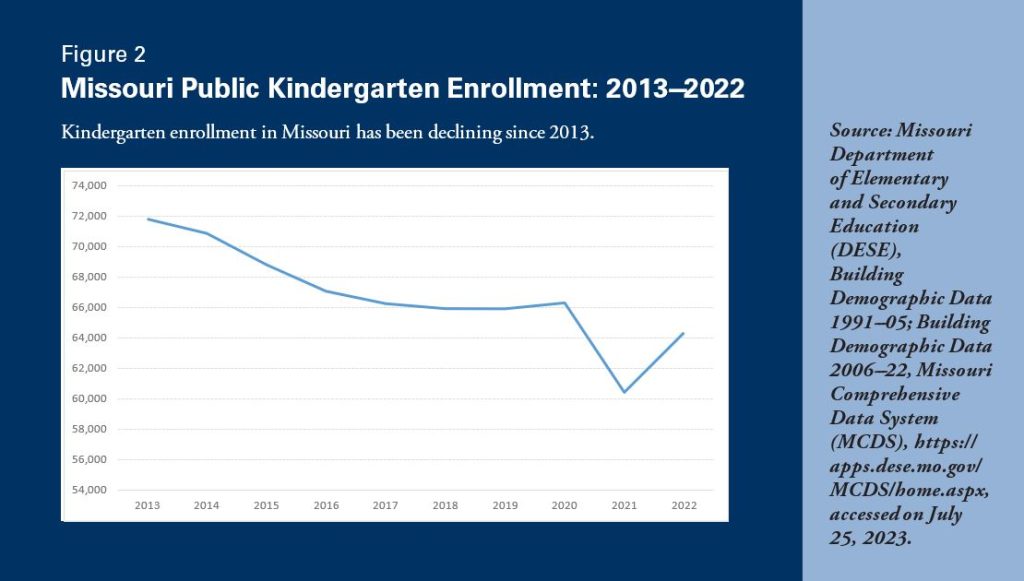

The decline can be seen by looking at cohorts of students starting kindergarten (see Figure 2). Missouri’s trends are very similar to national ones. Birth rates in the United States reached their peak in 2008 (excluding the post World War II baby boom 80 years ago) and have been declining since.14 Not surprisingly, Missouri’s largest kindergarten cohort started school in 2013. Since then, the number of kindergartners has been steadily declining.

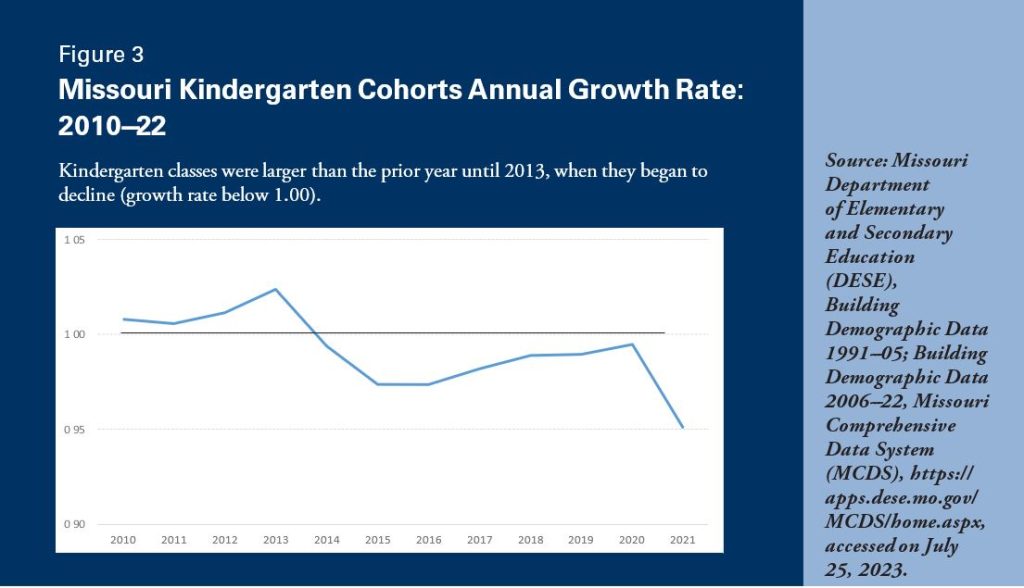

These enrollment numbers can be translated to percentage growth (or loss) in the size of the cohort. Figure 3 contains the growth or loss in the size of the kindergarten cohort compared to the prior year. A change of 1.00 means that the class size is the same in both years. A number below 1.00 means that the class size is smaller.

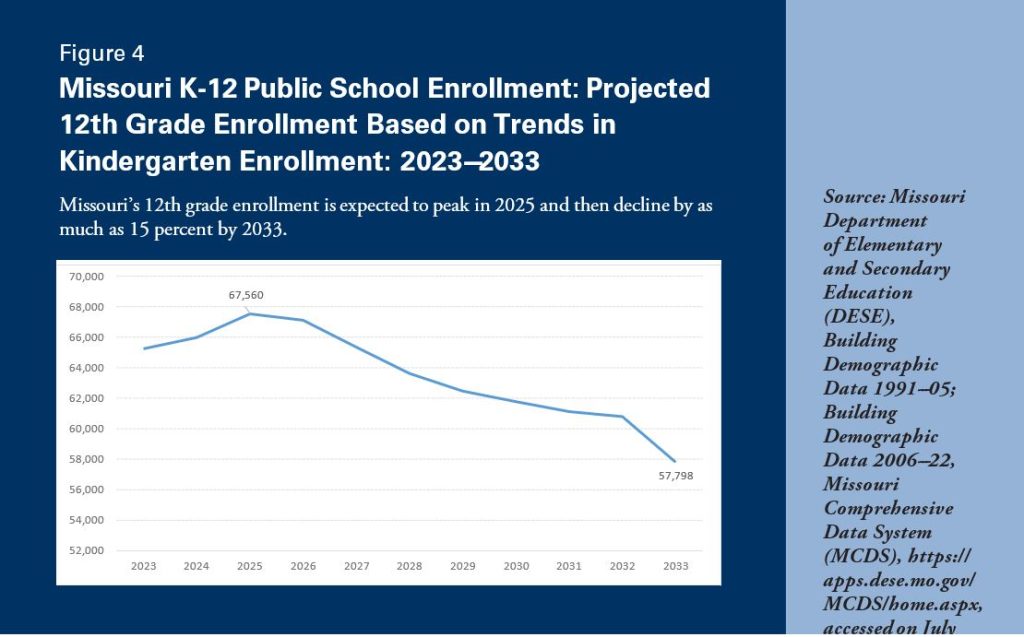

These changes in the size of kindergarten classes can be used to project the number of seniors in high school through 2033 (see Figure 4). After hitting a projected peak of over 67,500 12th graders in 2025, Missouri can expect, based on current information, a decline of 15 percent in that cohort by 2033. Fewer 12th graders means fewer Missourians entering college or career training and, eventually, the workforce. Of course, this is just a measure of the number of people available without regard to their skills, their likelihood of obtaining a postsecondary credential, or trends in labor force participation.

ACADEMIC TRENDS IN MISSOURI

In addition to demographic trends, there are academic trends occurring in Missouri that could signal trouble for the future of the workforce. Although Missouri tests its students in grades 3–8 every year, as required by the federal Department of Education, those tests have changed multiple times in the last decade, making it very difficult to make apples to apples comparisons over time. Therefore, this analysis is based on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), also known as the Nation’s Report Card. The NAEP reading and math assessments are administered every other year to representative samples of 4th and 8th graders in each state. Because the test uses a uniform framework and the same test is administered to every state, comparisons can be made over time and between states.15

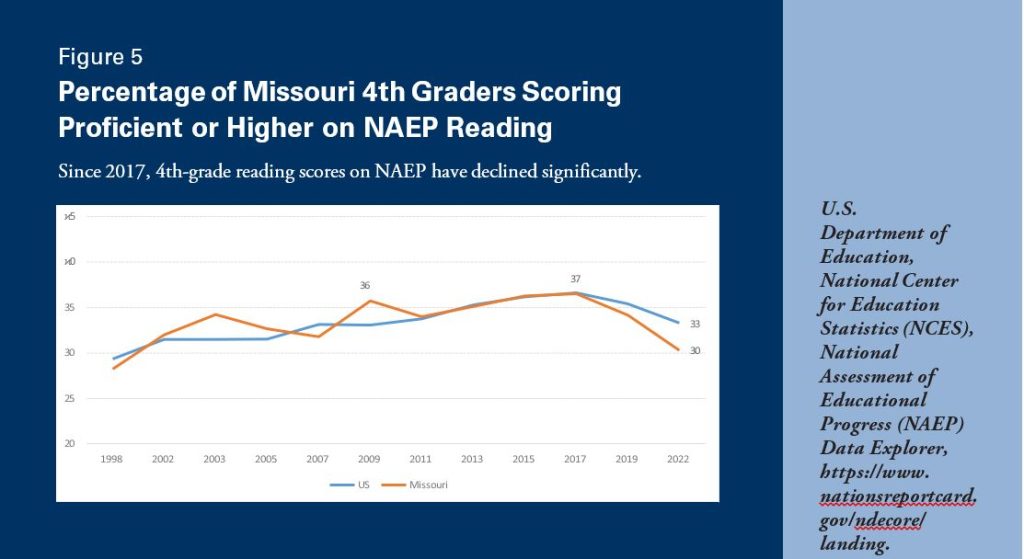

Although Missouri’s NAEP reading scores have generally tracked to nationwide scores, they recently fell below the national average. In addition, 4th-grade scores, which had been generally improving over the last twenty years, began to decline in 2017 (see Figure 5). In 2022, just 30 percent of Missouri’s 4th graders scored Proficient or higher, generally the equivalent of being on grade level, in reading. Those students will be in 8th grade in 2026 and graduating from high school in 2030.

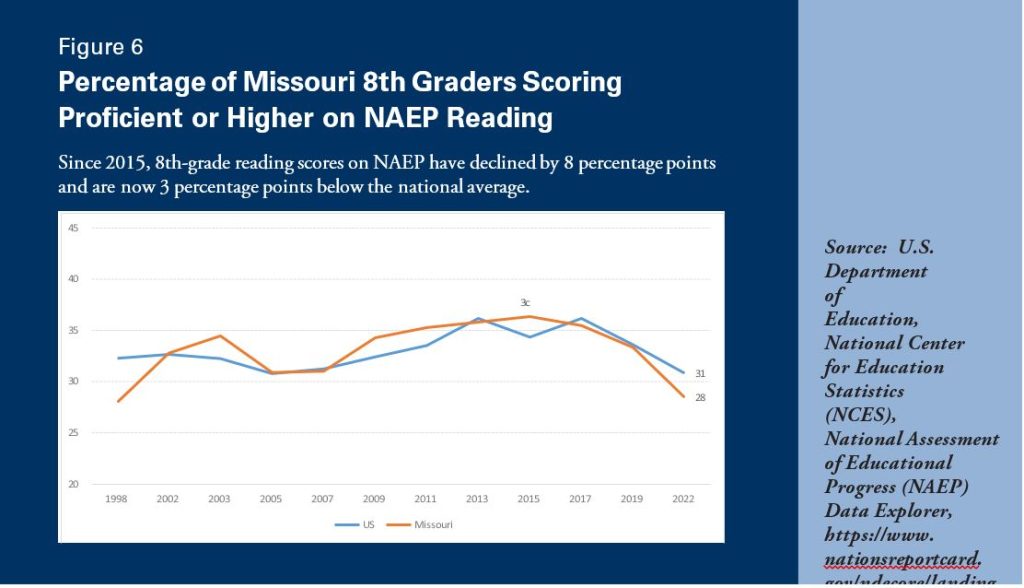

Unfortunately, the 8th-grade results are worse. In 2022, just 28 percent of Missouri 8th graders scored Proficient or higher on NAEP reading, a decline of 8 percentage points since 2015 (see Figure 6). Those students will be graduating from high school in 2026, just as the number of 12th graders is expected to be declining.

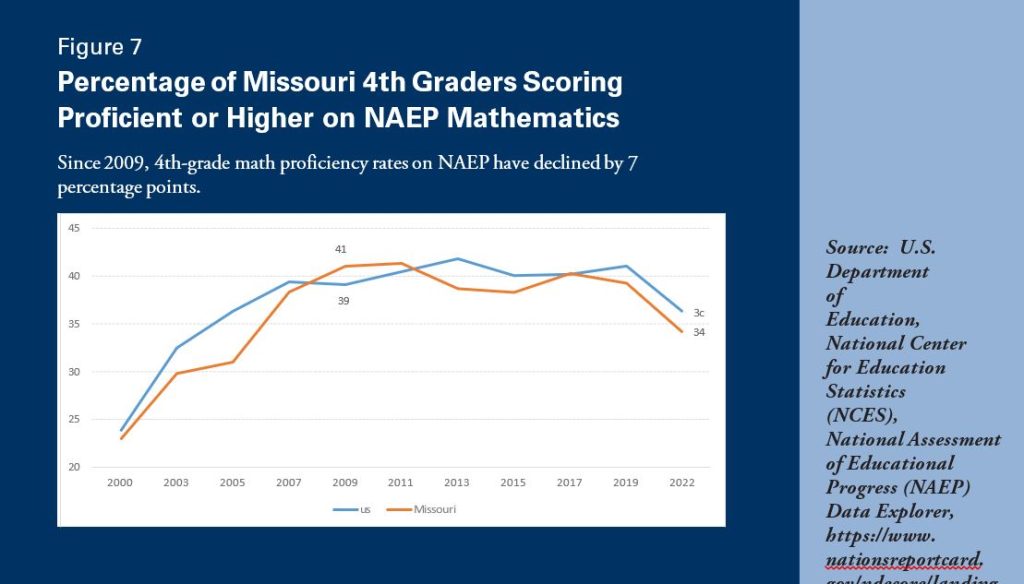

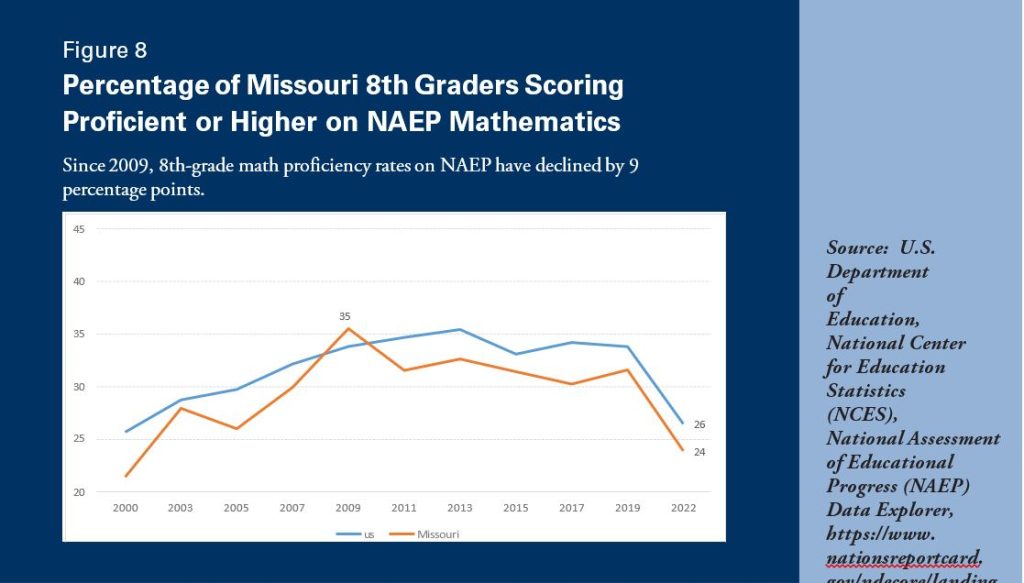

The numbers are similar for mathematics. In 2009, 41 percent of Missouri 4th graders scored Proficient or higher in math, which was higher than the U.S. average. By 2022, that number had dropped to 34 percent, lower than the national average (see Figure 7). In 2009, 35 percent of Missouri 8th graders scored Proficient or higher in math, a number that declined to just 24 percent by 2022 .

Combining these two trends is what tells the story. In 2009, there were over 68,000 8th graders in Missouri. Thirty four percent, or 23,100, scored Proficient or higher in reading and 23,800 scored Proficient or higher in math. In 2026, based on the kindergarten cohort from 2018, the total number of 8th graders is likely to be below 64,500. If proficiency rates stay at 2022 levels, fewer than 15,500 will be Proficient in math and just over 18,000 will be in reading. In other words, the number of students starting high school in 2027 on grade level will be almost one- third lower in math and one-quarter lower in reading. Can we expect the more than 40,000 remaining students to make up ground in high school in order to be college or career ready?

COLLEGE AND CAREER READINESS TRENDS

Obtaining a high school diploma is certainly an important step towards adulthood. However, if a student graduates from high school without being ready for college or a career, the diploma indicates little more than time served. What does it mean for a high school graduate to be college or career ready?

DESE measures college or career readiness (CCR) as part of its school accountability system, the Missouri School Improvement Program (MSIP). Although Missouri is currently on the sixth iteration of MSIP, measures of CCR have been consistent. Each school or district’s CCR score is the percentage of graduates who scored at or above the state standard on any department-approved assessment, such as the ACT, SAT, Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), ACT WorkKeys (a measure of career skills), or the ACCUPLACER (a college course placement exam).16 Examples of passing scores are a 22 on the ACT or an 1100 on the SAT.

While DESE does not seem to have published a statewide CCR score since 2017, it is possible to take the percentage of graduates in each district who met the standard and multiply that by the number of graduates in each district to calculate the number. In 2019, there were 61,051 students who graduated and 36,552 of them (60 percent) met a CCR benchmark. Similarly, in 2022 there were 61,195 graduates and 37,156 (61 percent) met a CCR benchmark. What happens to the over 24,000 high school graduates who received a diploma, but did not meet any college or career readiness benchmark? And what will be the impact as the number of graduates continues to decline along with the number of 18-year-olds who are college or career ready?

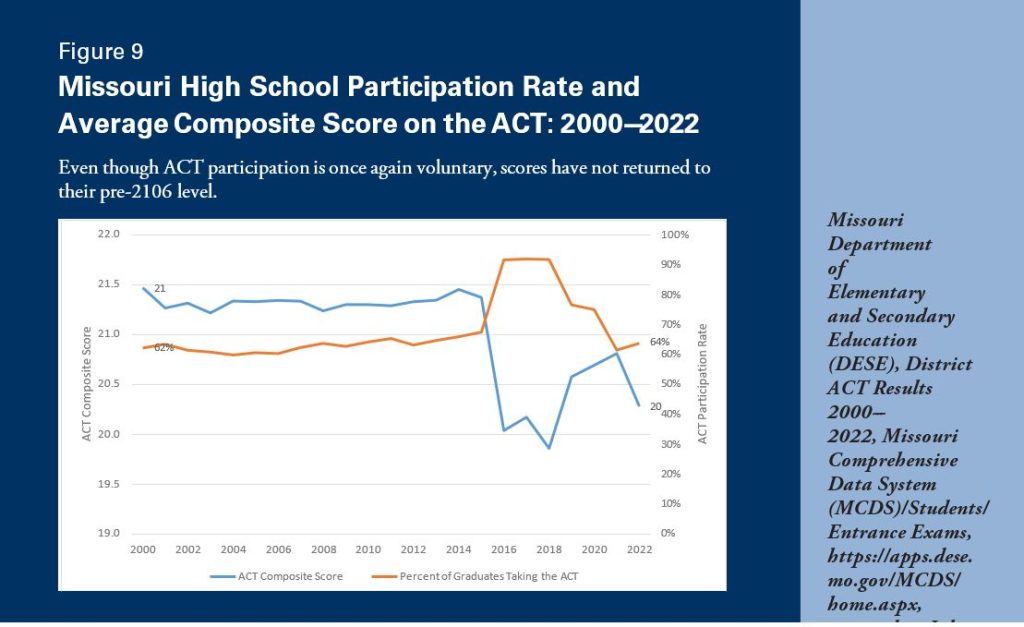

Two of the measures of the CCR score are the ACT exam and the Advanced Placement program. The ACT exam is an entrance exam used by most colleges and universities to make admissions decisions. In the Midwest, it is more common for college-bound students to take the ACT than to take the College Board’s SAT entrance exam. Many states, including Missouri (for two years), made the ACT compulsory as part of their state accountability system. In Missouri, the ACT was required and paid for by the state for all graduating seniors in 2016–17 and 2017–18.17

The orange line in Figure 9 reflects this change and the aftermath. Prior to the mandatory years, 60 to 65 percent of graduating seniors in Missouri took the ACT. Since the high of more than 90 percent participation in the two years that the state required it, participation rates have settled back to 64 percent. Scores, however, have not followed a similar track. Prior to 2016, average ACT composite scores were consistently around 21.3. However, composite scores have dropped by more than a point, even as the test has become voluntary once again, suggesting that college readiness has declined.

The College Board’s Advance Placement (AP) program allows high school students to take college-level courses. At the end of each AP class there is an exam through which students can earn college credits. The exams are scored on a 1–5 basis, with a 3 being considered passing. In 2022, over one third (34.6 percent) of high school students took an AP exam, and 21.6 percent scored a 3 or higher on at least one exam.18 Nationally, participation in AP has increased by 4.5 percentage points since 2012.

Missouri’s participation in this program is well below the national average. In 2022, just 20.6 percent of Missouri high school students took an AP exam, which ranked 45th among the 50 states, plus Washington, D.C. However, participation has increased by 5.6 percentage points in the last decade. Similarly, Missouri ranked 43rd in the percentage of students with a passing score on an AP exam, with just 12.1 percent of high school students in the state hitting that mark in 2022. Essentially, 88 percent of Missouri’s high school students are forgoing the opportunity to receive college credit through the AP program while in high school.

Turning to career readiness, it is difficult to determine both participation in or success in Missouri’s career and technical education (CTE) programs. Participation is reported by courses, with students who take multiple courses being counted more than once. However, in 2021, about two thirds of Missouri high school students took at least one CTE course, with a total of 309,985 courses taken.19 Outcomes are what matter, however. One measure of success in a CTE program is earning an industry- recognized credential (IRC). These are confirmation of an individual’s qualifications and are verified by a third party. Examples of IRCs include the Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) certificate and the Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) credential. In the 2022 school year, 8,631 Missouri high school students received an IRC prior to graduation.20

Missouri’s high school CTE certificate goes further. It requires that students meet eight criteria–earn a high school diploma, complete at least three courses in a single CTE program of study, maintain at least at 3.0 GPA, earn an IRC, complete at least 50 hours of appropriate work-based learning experiences, have at least a 95 percent attendance record, demonstrate employability skills, and achieve a passing score on one of the state’s measures of college or career readiness.21 In 2022, some 4,917 Missouri high school graduates earned the CTE certificate, which was 7.6 percent of graduates.

The low percentages of Missouri students in 2022 graduating class scoring above the national average on the ACT (31.8 percent), passing an AP exam (12.2 percent), attaining an IRC (13.3 percent), or earning a CTE certificate (7.6 percent) raises concerns about the quality of the future workforce. Taken in combination with the expected decline in the size of future graduating classes, these numbers would need to be significantly improved if Missouri is going to gain ground.

POSTSECONDARY TRENDS

One measure of workforce quality is the attainment of postsecondary degrees. As was previously mentioned, the percentage of Missouri’s workforce with either a bachelor’s degree or master’s degree has been declining in the last couple of years. The percentage of high school graduates who choose to enroll in college right after high school has also been declining.

According to the previously mentioned report from Missouri’s Coordinating Board for Higher Education, postsecondary enrollment of recent high school graduates has declined from 35 percent in 2012 to under 30 percent in 2022 (see Figure 10).22 Because the size of the graduating classes has been steady at around 64,000, this also means a decline in the number of students enrolling. In addition, the mix of enrollment has changed from a higher percentage choosing a 4-year program to an even split between 2-year and 4-year institutions.

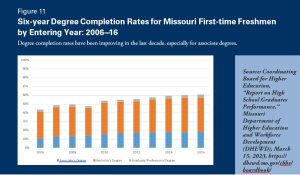

Although enrollment in postsecondary institutions has been declining, persistence and degree attainment has been improving, primarily at the associate degree level.23 Degree completion in this case is measured by the number of first-time freshmen enrolled full time who complete a degree within six years. In Figure 11, the degree completions for 2006 are for the students who started college in 2006 and completed a degree by 2012. Of the 64,300 graduates in the class of 2016, just over 13,000 had earned a postsecondary degree by 2022. Of course, this misses students who went to college out of state or who transferred. MERIC estimates that the state will add over 80,000 jobs that require a postsecondary degree by 2028. Those jobs will be difficult to fill with our current performance, particularly given the expected decline in the number of graduates.24

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

In 2019, Governor Parson issued multiple executive orders and announced “a new approach to economic and workforce development.”25 The new approach involved several programs directed at adult learners, such as Missouri One Start, the Fast Track Workforce Incentive Grant, and Missouri Works Training. These programs are designed to help put postsecondary degrees or certificates into the hands of workers who didn’t pursue them directly after high school. But wouldn’t it make sense to set more Missouri children on the right path when they’re still in school rather than try to remediate them later? Below are some ideas that could help put our students in a better position to enter college or the workforce once they’re done with K-12 education.

In 2019, Governor Parson issued multiple executive orders and announced “a new approach to economic and workforce development.”25 The new approach involved several programs directed at adult learners, such as Missouri One Start, the Fast Track Workforce Incentive Grant, and Missouri Works Training. These programs are designed to help put postsecondary degrees or certificates into the hands of workers who didn’t pursue them directly after high school. But wouldn’t it make sense to set more Missouri children on the right path when they’re still in school rather than try to remediate them later? Below are some ideas that could help put our students in a better position to enter college or the workforce once they’re done with K-12 education.

Early Literacy

Early Literacy

In 2022, just 30 percent of Missouri students were on grade level in reading, according to NAEP. This is deeply concerning, given that children generally learn to read through the third grade and then read to learn after that. States have begun putting intensive early literacy programs in place that are paying off. Mississippi, for example, has raised its NAEP 4th-grade reading score by 11 points since it put an intensive early literacy program

in place in 2013.26 An intensive early literacy program has early literacy screenings, individualized student literacy plans, teacher training with scientifically based reading instruction, and mandatory retention of third graders who read severely below grade level. Putting these policies in place in Missouri now could help reverse the negative impact on the future workforce.27

Competency-based Education

There is an opportunity to shift to competency-based education (CBE) on a large scale so that students don’t advance until they have mastered their coursework. CBE allows students to move through grade-level material at their own pace, with competency-based assessments throughout the year.28 In addition to routine assessments to identify content not yet mastered, CBE would prevent students from advancing through grades until they are ready to move on.

Incentives for Earning IRCs and Passing AP Exams

Missouri has been missing the mark on high school students getting college-level coursework or IRCs. One approach that could change that would be to offer financial incentives to districts for each student who passes an AP exam or earns an IRC. Some states, such as Kansas, simply give districts $500 for each IRC earned.29 Others, such as Florida, differentiate the incentive payment based on the value of the IRC. Similarly, several states have established Advanced Placement Incentive Programs (APIP).30 APIPs give cash incentives to both students and teachers for scores of 3 or higher on AP exams. According to a recent analysis, APIPs increase participation in AP programs and lead to other educational outcome improvements, such as college enrollment.

Open Enrollment and Open Course Taking

For many students, college or career readiness is impacted by being unable to tailor their education beyond their assigned public school. Much of Missouri is rural, and there are dozens of high schools with fewer than 100 students that are only able to offer a limited selection of courses. Yet there is no program that would allow students to enroll in-person in neighboring districts full time, or even at a program or class level. To address this problem for rural schools, Texas created the Rural Schools Innovation Zone (RSIZ).31 There are currently five academies (high schools) across three neighboring districts in the RSIZ—each with a unique focus, such as STEM or CTE. Students in these districts have access to five times more programs than at their assigned high school. Allowing Missouri’s students to choose between programs in their region would similarly expand their opportunities and positively impact the future workforce of the state.

Changes to the Funding Formula

For open enrollment to be effective, Missouri needs to restructure public education finance to fund students and not schools. Particularly in the post-pandemic era, students have grown comfortable with navigating between in-person, virtual and hybrid models. While “cafeteria style” education may not be around the corner, students and families are beginning to express a desire for it. Maximizing the experience of a public education student is different for every student—it can change year to year, it can change within a school year, and it can be different for children in the same family. It’s time for public education funding to reflect that. During 2023 alone, more than five states created programs that let every family use their state education funding at the public or private school of their choice. These programs often include a digital account for each student where state funds are deposited and the family determines how the money is spent. The need for flexibility like this is only going to grow. Allowing high school students to use public funding to put together a program that may include college coursework, apprenticeships, or internships, to name just a few different options, will lead to a stronger workforce.

CONCLUSION

One doesn’t need a crystal ball to see where the Missouri workforce is headed. The state has a declining number of elementary and secondary students, and the percentage of those students who can do reading or math on grade level is also going down. Currently, four in ten high school students graduate with a diploma, but no indication of college or career readiness. Despite directing attention and money to building career skills, fewer than eight percent of high school students complete the state’s CTE program. The percentage of high school students who enroll in college the fall after graduation is declining, particularly for four-year institutions. And the percentages of Missouri adults with either a bachelor’s or graduate degree are going in the wrong direction.

Steps need to be taken now to turn these trends around. Early literacy and numeracy can’t wait for another generation of Missouri children. We need strong programs with teeth. Students should no longer be able to advance through the system without mastering the material. State leadership should focus on the structure and design of the K-12 system so that students can find a good educational fit. And the funding system that worked for the last century of mandatory assignment and school board power needs to be replaced with a student-centered one. Missouri can once again become an engine of growth for business and families, but the work needs to start now.

NOTES

- S. Census Bureau, Bachelor’s Degree or Higher for Missouri [GCT1502MO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred. stlouisfed.org/series/GCT1502MO, July 20, 2023.

- Cohn, Scott. “These 10 states are America’s best at producing the workers that employers want to hire,” CNBC, July 17, 2023, https://www.cnbc.

com/2023/07/17/these-10-states-are-americas-best-for- workers-employers-want-to-hire.html

- Fast Track Workforce Incentive Grant, Missouri Department of Higher Education & Workforce Development, https://dhewd.mo.gov/initiatives/ php#:~:text=The%20 Fast%20Track%20grant%20is,uniforms%20are%20 covered%20for%20apprentices.

- S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Concepts and Definitions, https://www.bls.gov/cps/definitions. htm#:~:text=The%20labor%20force%20includes%20 all,or%20actively%20looking%20for%20work, accessed on July 25, 2023.

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/missouri- population

- S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees: Total Nonfarm in Missouri [MONA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred. stlouisfed.org/series/MONA, July 24, 2023.

- S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Participation Rate for Missouri [LBSSA29], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https:// fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LBSSA29, July 25, 2023.

- MERIC, “Missouri Jobs by Education and Skill Levels,” Missouri Department of Higher Education and Workforce Development, May 2021, https://meric. gov/media/pdf/missouri-jobs-education-and-skill- level

- S. Census Bureau, Bachelor’s Degree or Higher for Missouri [GCT1502MO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GCT1502MO, July 20, 2023.

- S. Census Bureau, People 25 Years and Over Who Have Completed a Graduate or Professional Degree for Missouri [GCT1503MO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred. stlouisfed.org/series/GCT1503MO, July 25, 2023.

- FRED Economic Data, People 25 years and over who have completed a graduate or professional degree for Missouri, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ GCT1503MO

- Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), Building Demographic Data 1991-05; Building Demographic Data 2006-22, Missouri Comprehensive Data System (MCDS), https://apps.dese.mo.gov/MCDS/home.aspx, accessed on July 25, 2023.

- Livingston, Gretchen and Cohn, D’Vera. “US Birth Rate Decline Linked to Recession,” Pew Research Center, April 6, 2010. https://www.pewrorg/ social-trends/2010/04/06/us-birth-rate-decline-linked- to-recession/

- US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), nces.ed.gov/ nationsreportcard/

- Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), MSIP 6 Comprehensive Guide to the Missouri School Improvement Program, updated 7/19/2023, https://dese.mo.gov/media/pdf/msip-6- comprehensive-guide

- Levin, “Missouri to no longer offer free ACT tests,” Joplin Globe, July 12, 2017, https://www. joplinglobe.com/news/local_news/missouri-to-no- longer-offer-free-act-tests/article_dfa55d32-2431- 5223-b033-33b9f004b77c.html

- AP Program Results: Class of 2022, College Board, https://reports.collegeboard.org/ap-program-results/ class-of-2022

- Office of Career and Technical Education (CTE), Career and Technical Education Program/CourseEnrollment Data 2021-2022, Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), https://dese.mo.gov/media/pdf/2021-22-enrollment- report

- Office of Career and Technical Education (CTE), “Career and Technical Education in Missouri: Show Me Learning that Works,” Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), https:// mo.gov/media/pdf/ccr-career-ed-fact-sheet

- Office of Career and Technical Education (CTE), Certificate Criteria, Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), https:// mo.gov/media/pdf/cte-certificate-criteria

- Coordinating Board for Higher Education, “Report on High School Graduates Performance,” Missouri Department of Higher Education and Workforce Development (DHEWD), March 15, 2023, https:// mo.gov/cbhe/boardbook/Tab70316.pdf%20

- MERIC, “Missouri Jobs by Education and Skill Levels,” Missouri Department of Higher Education and Workforce Development, May 2021, https:// mo.gov/media/pdf/missouri-jobs-education- and-skill-level

- Press release, “Governor Parson announces new approach to economic and workforce development, calls for reorganization of state government,” Office of the Governor, January 17, 2019, https://governor. gov/press-releases/archive/governor-parson- announces-new-approach-economic-and-workforce- development

- ExcelinEd, Early Literacy – Ensuring all children can read by fourth grade, https://excelined.org/policy- playbook/early-literacy/

- Frank, Avery. “The Science of Reading in Missouri,” Show-Me Institute, June 26, 2023, https:// org/blog/performance/the-science-of- reading-in-missouri/

- Rix, Kate. “Competency-based education: What is it and how it can boost student engagement,” US News, March 22, 2023, https://www.usnews.com/education/ k12/articles/competency-based-education-what-it-is- and-how-it-can-boost-student-engagement

- Credential Currency – How states can identify and promote credentials of value, Education Strategy Group, September 2018, https://ccsso.org/sites/ default/files/2018-10/Credential_Currency_report.pdf

- Jackson, C. Kirabo. “Cash for test scores,” Education Next, Vol. 8, No. 4, Summer 2023, https://www.educationnext.org/cash-for-test- scores/#:~:text=The%20National%20Math%20 and%20Science%20Initiative%20awarded%20 grants,these%20programs%20to%20150%20 districts%20across%2020%20states.

- Rural Schools Innovation Zone, Reinventing the rural education experience, https://www.thersiz.org/our- mission-vision

5297 Washington Place I Saint Louis, MO 63108 I 314-454-0647 1520 Clay Street, Suite B-6 I North Kansas City, MO 64116 I 816-561-1777

Visit Us: showmeinstitute.org

Find Us on Facebook: Show-Me Institute

Follow Us on Twitter: @showme

Watch Us on YouTube: Show-Me Institute