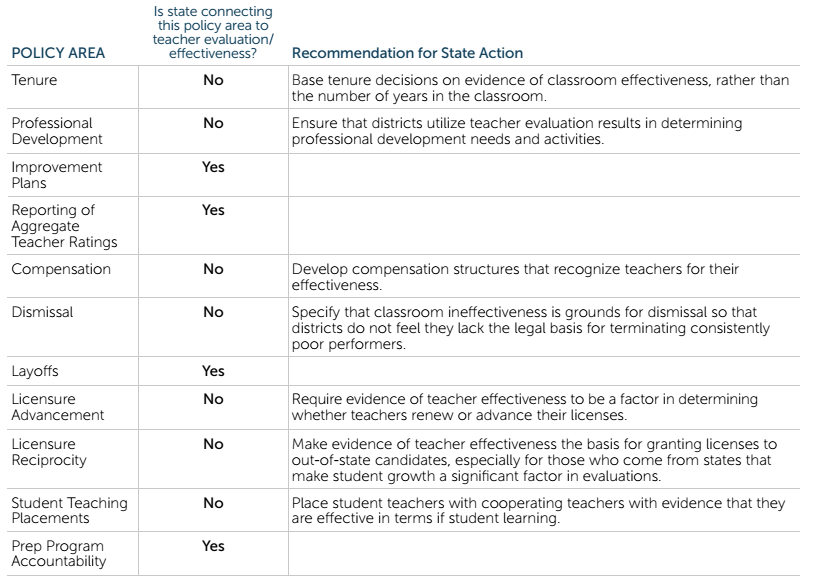

The National Council on Teacher Quality is out with its annual state-by-state report on teacher policy. I’m still digging through all of the findings, but I do want to bring your attention to the table shown above (which appears on page 63 of the report), wherein the authors take a big-picture look at Missouri education policy and ask if it is oriented toward identifying and rewarding the most effective teachers.

What does this mean?

· Missouri does not base tenure decisions on demonstrated teacher effectiveness

· Missouri does not ensure that districts use teacher evaluation results when selecting professional development activities.

· Missouri does not pay better teachers more.

· Missouri does not specify that ineffectiveness is grounds for dismissal for teachers or principals.

· Missouri does not require that teacher effectiveness be taken into account when teachers are looking to renew their licenses.

· Missouri does not make evidence of teacher effectiveness the basis for granting Missouri licenses for teachers with licenses from out of state.

· Missouri does not place its student teachers in classrooms with teachers that have demonstrated effectiveness.

I’ll be the first to say that student test scores should not be the sole measure of a teacher’s effectiveness. An over-reliance on standardized tests has led to many unintended and unfortunate consequences. But two course corrections working in tandem—rethinking what tests we give children and how we use the results, and rethinking how we help recruit, reward, and retain great teachers—have a great deal of potential for improving Missouri’s education system.

If we’re going to have policies like licensure and tenure, they should be based on teacher effectiveness, not simply how long someone has been in the classroom. If districts are going to spend millions of dollars on professional development activities, the money should be in areas where teachers are struggling to improve student achievement.

Ultimately, a move towards a system with greater school choice would diminish the need for heavy-handed, centrally-driven teacher evaluation policies. Individual school leaders would be responsible for putting together the best possible staff so families would want to send their children to that particular school. Parents, who have access to detailed information both about their child and how well he or she is doing, would be the ultimate arbiters of teacher quality. But until such a system is in place, we must work harder to identify great teachers, recruit them into our schools, and then do what is necessary to keep them here.